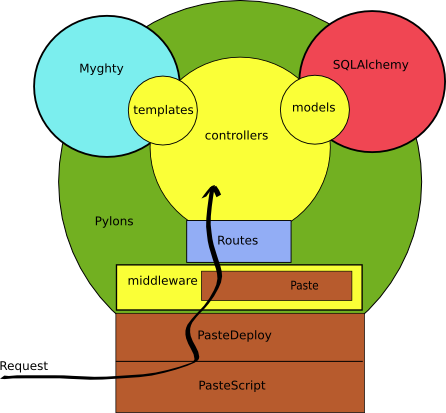

I scribbled this down on our whiteboard last Friday, trying to explain

how Pylons and Paste

fit together. Prevously jdub and Lindsay had

asked me similar questions. Until Friday, I wasn’t even sure myself.

The first thing to note is that Paste is not a framework or single

library, it’s a collection of components that by themselves don’t do a

lot, but with their powers combined form a set of useful and sometimes

essential tools for building a web application in Python.

Paste implements an interface known as WSGI, aka

the Web Server Gateway Interface. It’s defined in PEP

333. Basically WSGI

describes a Chain of Command design pattern; each piece of a WSGI

application takes a request, and either acts on that request or passes

it along the chain. The interface described by WSGI means you can

plug WSGI apps (or as Pylons calls them, /middleware/) together in any

order as you like.

Why is this useful? Well, it means you can take an off-the-shelf

authentication handler to cope with 403 and 401 responses and take

care of logins. One would only need to say “this is how you

authenticate someone” and “this is how you ask the user for their

password.” Other things are possible; Pylons ships with an ultra-sexy

500 handler that puts you in a DHTML debugger, complete with traceback

and Python interpreter. (Of course such a tool is a giant security

hole so it is easily turned off in production environments.)

So, that’s Paste. There’s a few special cases in there, though:

PasteScript and PasteDeploy. They’re special in that they tend to be

at the bottom of the stack – they’re specifically for launching WSGI

applications, configuration of the application (e.g. authenticatoin

details alluded to above) and connecting to the application

(e.g. direct HTTP, FastCGI, and other connectors). I suspect that my

diagram above doesn’t lend itself well to describing how PasteScript

and PasteDeploy really work; it’s still a bit of dark magic to me. I

hope someone else would be able to build on this article with their

own that rebuts the errors and clears the grey areas.

In a Pylons app, you tend not to notice Paste, except when deploying

(because you tend to run the command paster serve to

launch a development environment). Pylons itself is mostly just

glue. It’s a thin veil of a framework over the top of some very

powerful supporting libraries but presents them in a convenient and

well defined way.

When you create a Pylons app, you get your paste middleware built for

you, and then the entry point for your app is created as a WSGI

application too. So it sits on top of the stack, taking in requests,

and sending out responses. Your app can define its own middleware,

too, so you have a lot of control over what happens between your app

and the browser.

The main components of a Pylons app are:

A route mapper, by default Routes. The route mapper takes in URLs from the request passed into the app, and maps that URL to a controller object and method call. (If you’ve used RoR then you probably are familiar with this already.)

A templating engine, by default Myghty. The templating engine generates the view presented to the browser.

A data model. Pylons doesn’t prefer any method of data model, it just makes available a model module within which you can define your own data model. I use SQLAlchemy as an ORM because it is very powerful and is nicely suited to working with existing schemas. It works as an MVC between the data model presented to the application and the database schema itself.

Pylons lets you swap out any of these components with your own, if you

desire. I find Routes and Myghty to be powerful and flexible and

friendly enough that there’s no reason to want anything else.

Your controller objects, like any MVC pattern, coordinate between the

model and the view. An action performed on a controller retrieves

some data from the model, possibly altering it, and renders that data

using the template engine.

There are other parts, other libraries that you’ll see in a Pylons

app, that aren’t represented here. WebHelpers is a library of

convenience functions used in the template engine, for generating

common HTML and JavaScript. paste.fixture is a web app test

framework that takes advantage of the common interface of WSGI to

allow one to test their application without requiring a full web

server and socket handling. FormEncode

handles form validation, useful from within a controller object.

These are but to name a few.

Unfortunately there is a sore need for overviews like this one in the

Paste and Pylons community; as stated earlier I didn’t fully

understand the relationships myself until I came up with this diagram.

Hopefully then, dear reader, you have a better insight into how this

collection of names fit together, and can avoid the steep learning

curve :-)